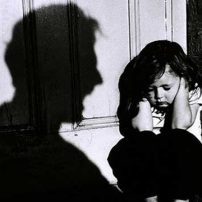

Practices of physical punishment in children lead to the removal of parental care

JUDGMENT

Tlapak and others v. Germany 22.3.2018 (no. 11308/16 and 11344/16) and Wetjen and others v. Germany (no. 68125/14 and 72204/14)

SUMMARY

Church of the Twelve Tribal Church and corporal punishments from parents to children. Established violence against minors (beating with a cane), which parents considered a necessary element in bringing up children. Parental care removal by parents. No violation of respect for private and family life. Ensuring fair satisfaction for the unreasonable length of internal proceedings in part of the applicants.

PROVISION

Article 8

PRINCIPAL FACTS

Both cases concerned four families who are members of the Twelve Tribes Church (Zwölf Stämme), living in two communities in Bavaria (Germany). The applicants in the first case are the parents of the Tlapak and Pingen families, who resided previously in the Wörnitz community.

The applicants in the second case are the parents and children of the Wetjen and Schott families, who used to live together in the Klosterzimmern community. In 2012 the press reported that the Twelve Tribes Church punished their children by caning. A year later a television reporter sent video footage, filmed with a hidden camera, to the local child welfare services and the Nördlingen Family Court, showing the caning of various children between the ages of three and 12.

At the request of the child welfare services, the family courts brought interim custody proceedings regarding all children in the Twelve Tribes communities, including the eight Tlapak, Pingen, Wetjen and Schott children. They based their decisions on the press reports as well as statements by former members of the church. The courts withdrew certain of the parents’ rights, including making decisions on their children’s place of residence, health and schooling, and in September 2013 the welfare services took the communities’ children into care. Some of the children were placed in children’s homes, others in foster families.

After the four families’ children had been taken into care, the family courts initiated main proceedings concerning custody and commissioned psychologists’ expert opinions.

In the proceedings before the European Court, the Wetjen and Schott families complained about the interim proceedings and the Tlapak and Pingen parents complained about the main proceedings. In both sets of proceedings, the courts concluded that caning constituted child abuse and that taking the children into care had been justified by the risk of the children being subjected to such abuse while living with their parents.

The courts established this risk after having heard the parents, the children (except for two who were too young to be questioned), the children’s guardians ad litem and representatives of the youth office. In the Tlapak and Pingen families’ case, the courts also heard the psychologist who had been commissioned to draw up a report as well as the expert commissioned by the applicants. In the Wetjen and Schott families’ case, which concerned the interim proceedings, the courts deferred the psychologist’s conclusions to the main proceedings. The courts also gave detailed reasons why there was no alternative option to protecting the children, other than taking them into care. In particular, during the proceedings the parents remained convinced that corporal punishment was a legitimate child-rearing method. Even if the parents themselves would agree to no caning, there was no way of ensuring that other members of the community would not carry out such punishment on their children.

Both sets of proceedings ended in August 2015 and May 2014 with the Federal Constitutional Court’s refusal to admit the applicants’ complaints. The Tlapak parents moved to the Czech Republic in 2015 and have been living there since, without their son, who remained in care. The court order concerning the Pingens’ son was temporarily lifted in December 2014 because he was just one year and six months old, and was still being breastfed. The Pingens other children, two daughters, remained in foster care. The Schotts’ eldest daughter returned to the community in December 2013 as she was 14 years’ old and no longer at risk of being caned. The Schotts’ remaining two daughters and the Wetjens’ son remained in care at the end of the interim proceedings.

THE DECISION OF THE COURT

Length of the proceedings

The Court rejected as inadmissible the Tlapak and Pingen parents’ complaint that the main custody proceedings had been excessively long. The proceedings had taken one year and 11 months, during which time the Family Court could not be held responsible for any particular delays. On the contrary, the court had been active: it had commissioned a psychologist’s opinion, heard the applicants, their children and further witnesses and led negotiations for a settlement between the applicants and the youth office.

In view of the Government’s declaration recognising that there had been a violation of Article 8 concerning the length of the interim proceedings, namely from September 2013 to May 2014, in the Wetjen and Schott families’ cases and proposing compensation, the Court decided to strike out of its list of cases those parts of the applications.

Withdrawal of parental authority

First the Court found that the decisions to withdraw some parental rights had constituted an interference with the applicants’ right to respect for their family life. The decisions, based in national law and on the likelihood that the children would be caned, had aimed at protecting the “rights and freedoms” of the children.

Furthermore, the Court was satisfied that the decision-making process in the cases had been reasonable. The applicants, assisted by counsel, had been able to put forward all their arguments against withdrawal of parental authority. The courts had had the benefit of direct contact with all those concerned and had diligently established the facts. Even though the Tlapaks and Pingens had withdrawn their consent for the psychologists’ opinion to be used as evidence in the proceedings, the Court considered that it had been justified for the German courts to use the opinion given the general interest at stake, namely the effective protection of children in family court proceedings. It also found it acceptable that the family courts had not awaited the conclusions of the psychologist concerning the Wetjens and the Schotts in the interim proceedings, given the need for particular speediness in such proceedings.

Although taking children into care and splitting up a family constituted a very serious interference with the right to respect for family life and should only be used as a last resort, the domestic courts’ decisions had been based on a risk of inhuman or degrading treatment, which is prohibited in absolute terms under the European Convention. The courts had taken an individualised approach, taking into account whether each child was of an age where they were at risk of corporal punishment. The courts had also given detailed reasons why there had been no other options available to protect the children and the Court agreed with those conclusions. Moreover, the proceedings had concerned a form of institutionalised violence against minors, considered by the applicant parents as an element of the children’s upbringing. Consequently, any assistance by the youth office, such as training the parents, could not have effectively protected the children, as corporally disciplining the children had been based on their unshakeable dogma.

Therefore, based on fair proceedings, the domestic courts had struck a balance between the interests of the applicant parents and the best interests of the applicant children which did not fall outside the domestic authorities’ wide room for manoeuvre (“margin of appreciation”) when assessing the necessity of taking a child into care.

Just satisfaction (Article 41)

In the case of Wetjen and Others, the Court, taking note of the Government’s declaration recognising that there had been a violation of Article 8 as concerned the length of the interim proceedings, directed that Germany was to pay the Wetjens 9,000 euros (EUR) and the Schotts EUR 8,000 in respect of pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage as well as costs and expenses (echrcaselaw.com editing).