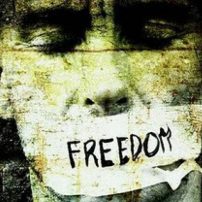

Editor’s liability for defamation violated his right to freedom of expression

JUDGMENT

Olafsson v. Iceland 16-3-2017 (no. 58493/13)

SUMMARY

The applicant, Mr Ólafsson, was an editor of the web-based media site Pressan. He published articles insinuating that a political candidate had committed sexual abuse against children. The Supreme Court of Iceland held Mr Ólafsson liable for defamation. He complained to the European Court of Human Rights that this liability had violated his right to freedom of expression.

In today’s Chamber judgment in the case of Olafsson v. Iceland (application no. 58493/13) the Court held, unanimously, that there had been a violation of Article 10 (freedom of expression) of the

European Convention on Human Rights.

In particular, the Court held that the liability for defamation had not been necessary in a democratic society, given the circumstances of the case. The subject of the allegations had been standing for political office and should have anticipated public scrutiny. The articles about him had been published in good faith, in compliance with ordinary journalistic standards, and had contributed to a debate of public interest. Whilst the allegations had been defamatory, they were being made not by Mr Ólafsson himself, but by others. The political candidate had chosen not to sue the persons

making the claims, and had thus perhaps prevented Mr Ólafsson from establishing that he had acted in good faith and had ascertained the truth of the allegations. Mr Ólafsson had also been ordered to pay compensation and costs. In these circumstances, the Supreme Court had failed to strike a reasonable balance between the measures restricting Mr Ólafsson’s freedom of expression, and the legitimate aim of protecting the reputation of others.

IMPORTANCE OF THE DECISION

Candidates in elections are public figures and have to expect criticism and public scrutiny greater than a simple individual.

PROVISION

Article 10

PRINCIPAL FACTS

The applicant, Steingrímur Sævarr Ólafsson, is an Icelandic national who was born in 1965 and lives in Reykjavik. At the relevant time, Mr Ólafsson was an editor of the web-based media site Pressan. Between November 2010 and May 2011, Pressan published a series of articles relating to allegations of child abuse against A, which had been made by two adult sisters with family ties to A. At the time of the first articles, A. was standing in the forthcoming Constitutional Assembly elections. The two sisters maintained that they had been sexually abused by him and suggested that he was not fit for public office. A. denied the allegations. One article stated that A.’s lawyer had contacted the sisters, offering to settle the matter, failing which A would bring defamation proceedings against them.

However, A. brought a defamation claim against Mr Ólafsson. At first instance, the court rejected the claim, essentially on the grounds that the statements made in the articles had been in the public interest, and Mr Ólafsson was not making the allegations himself but was merely disseminating them.

However, the Supreme Court overturned much of this judgment. It held the statements which had insinuated that A had committed child abuse had been defamatory. The court declared the

statements null and void, and ordered Mr Ólafsson to pay 200,000 Icelandic Krónur (approximately 1,600 euros) for non-pecuniary damage, and 800,000 Krónur (approximately 6,500 euros) in costs.

Whilst the court accepted that candidates for public service had to endure a certain amount of public scrutiny, it held that this could not justify the accusations of criminality against A. in the media – in particular, because A. had not been found guilty of the alleged conduct and had not been under investigation for it.

THE DECISION OF THE COURT

Article 10 (freedom of expression)

There will be a violation of Article 10 when there is an interference with an individual’s right to freedom of expression and this interference is not: prescribed by law, in pursuit of a legitimate aim,

or necessary in a democratic society. Both parties agreed that Mr Ólafsson’s liability for defamation had interfered with his freedom of expression, and that this had been in pursuit of a legitimate aim (namely, the protection of the reputation or rights of others). The questions for the Court were therefore whether the interference had been prescribed by law, and whether it had been necessary in a democratic society.

The Court held that the interference had been prescribed by law. The annulment of the statements and the imposition of non-pecuniary damages had been prescribed by the Penal Code and the Tort Act. The Supreme Court had referred to one of its previous judgments, case no.100/2011, and found that under domestic law Mr Ólafsson had been subject to an unwritten supervisory duty as an editor to prevent the publication of harmful content on the website. Taking into account the nature of the editorial activity in question, that the liability was foreseeable to Mr Ólafsson with appropriate legal advice, and the judgments of the Supreme Court, the Court held that Mr Ólafsson’s liability had been prescribed by domestic law.

In regard to the question of whether the liability had been necessary in a democratic society, it was necessary for the Court to assess whether there had been an appropriate balancing of the right to

respect for private life (under Article 8), and the right to freedom of expression (under Article 10). Given the circumstances of the case, an appropriate balance had not been struck by the Supreme Court. A. had been standing for political office and should have anticipated public scrutiny. The limits of acceptable criticism must accordingly be wider than in the case of a private individual. The articles about him had been published in good faith and in compliance with ordinary journalistic standards (in particular, the author of the articles had interviewed a wide range of people in order to examine the credibility of the sisters, and had also published A.’s claims that their allegations were false).

Furthermore, the articles had contributed to a debate of public interest, given that A. had been standing for public office and the issue of sexual violence against children is a serious topic of public

concern.

Whilst the allegations had been defamatory, they were being made not by Mr Ólafsson himself, but by the two sisters. They had already been published on the sisters’ website, and the statements held to be defamatory in Pressan were all verbatim renderings of the sisters’ own comments, which they confirmed had been accurately quoted. In so far as Mr Ólafsson’s liability may have been in the legitimate interest of protecting A. against the sisters’ defamatory allegations, that interest had been largely preserved by the possibility of A. suing the sisters themselves. Yet he had chosen not to sue the sisters – perhaps preventing Mr Ólafsson from establishing that he had acted in good faith and had ascertained the truth. Given his liability, Mr Ólafsson had been ordered to pay compensation and costs. Though this was not a criminal sanction, and the amount may not appear harsh, in the context of assessing proportionality what matters is the very fact of a judgment being made against him.

In the light of these considerations, the Court held that the arguments of the domestic courts, although relevant, could not be regarded as sufficient to justify the interference in issue. The

Supreme Court had not given due consideration to the principles and criteria laid down by the Court’s case law for balancing the right to respect for private life and the right to freedom of

expression. It thus exceeded the margin of appreciation afforded to it and failed to strike a reasonable balance of proportionality between the measures imposed, restricting the applicant’s

right to freedom of expression, and the legitimate aim pursued. There had therefore been a violation of Article 10.

Just satisfaction (Article 41)

The Court did not award Mr Ólafsson any just satisfaction, as he had not submitted a claim for any.